Now, the need to store power from renewable sources is reviving interest in this old technology in the U.S.

“Just in the past several years, 92 new projects have come into the development pipeline,” says Malcolm Woolf, president and CEO of the National Hydropower Association. Most of the projects, however, are in the planning stages and still need regulatory approval and financing.

Thanks to the climate bill that President Biden signed in August, these projects now qualify for the same 30 percent tax credit that solar and wind projects enjoy. “That is an absolute game-changer,” Woolf says. “A number of these projects that have been in the pipeline for a number of years now suddenly are a whole lot more bankable.”

Water batteries have a lot of competitors, when it comes to storing energy. Some companies, including the car company GM, are exploring ways for the electric grid to draw emergency power from the batteries in millions of privately owned electric cars. Others are working on ways to store electricity by compressing air or making hydrogen. Still others are focused on ways to manage the demand for electricity, rather than the supply. Electric water heaters, for instance, could be remotely controlled to run when electricity is plentiful and shut down when it’s scarce.

Pumping water, however, has some advantages. It’s a proven way to store massive amounts of power. The San Vicente project would store roughly as much electricity as the batteries in 50,000 of Tesla’s long range Model 3 cars. Water batteries also don’t require hard-to-find battery materials like cobalt and lithium, and the plants can keep working for more than a century.

The biggest problem with them, at least according to some, is that it’s hard to find places to build them. They need large amounts of water, topography that allows the construction of a lower and higher reservoir, and regulatory permission to disturb the landscape.

Woolf, however, says the perception of pumped hydro’s limited prospects “is a myth that I am working hard to disabuse folks of.” Pumped hydro facilities, he says, don’t have to be as massive as those of the past century, and they don’t need to disturb free-flowing streams and rivers. Many proposals are for “closed-loop” systems that use the same water over and over, moving it back and forth between two big ponds, one higher than the other, like sand in an hourglass.

Three of the proposed projects in the U.S. that appear closest to breaking ground, in Montana, Oregon, and southern California, all would operate as closed loops.

Kelly Catlett, director of hydropower reform at American Rivers, an environmental advocacy organization that has highlighted the environmental harm caused by dams, says that “there are good pumped storage projects, and there are not-so-good pumped storage projects.”

Her group won’t support projects that build new dams on streams and rivers, disrupting sensitive aquatic ecosystems. But San Diego’s plan, she says, “looks like something that we could potentially support” because it uses an existing reservoir and doesn’t disturb any flowing streams. Also, she says, “I’m unaware of any opposition by indigenous nations, which is another really important factor, as they have borne a lot of the impacts of hydropower development over the decades.”

The board of the San Diego County Water Authority, and San Diego’s city council, are expected to vote soon on whether to move ahead with a detailed engineering design of pumped hydro storage at the San Vicente reservoir. The state of California is chipping in $18 million. The design work, followed by regulatory approvals, financing, and actual construction, is likely to take a decade or more.

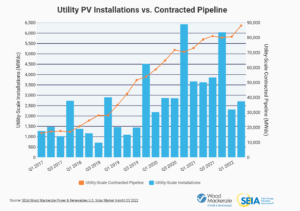

In 2023, the world added renewable energy at a breakneck pace, a trend that, if amplified, could help the planet move away from fossil fuels and prevent severe global warming.

In 2023, the world added renewable energy at a breakneck pace, a trend that, if amplified, could help the planet move away from fossil fuels and prevent severe global warming.

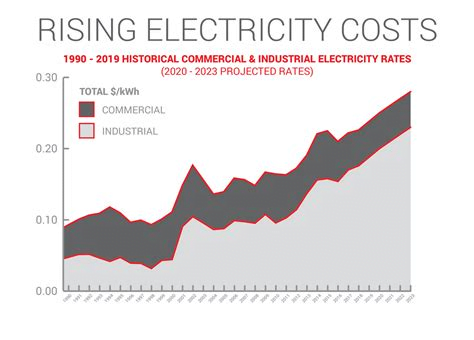

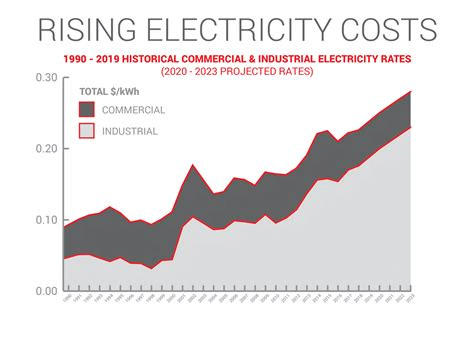

With the ever increasing costs for electric power, the high price of oil and the growing concern for the environment, many businesses are finding alternative sources of energy. Solar renewable energy is a sustainable choice and one that can be used in many commercial situations.

With the ever increasing costs for electric power, the high price of oil and the growing concern for the environment, many businesses are finding alternative sources of energy. Solar renewable energy is a sustainable choice and one that can be used in many commercial situations.